In his 2005 release ‘Taking a Walk’ things don’t go particularly well for John Prine’s subject; in fact at one memorable juncture in the song he laments: “I felt about as welcome as a Walmart superstore.” Well I’m happy to report that my frequent walks around here tend to end on a much more upbeat note. And I go on many of them; almost daily — with the sun well into the western sky — I set out on the local roads and tracks for a little jaunt. The main choice is: ‘motse kotsa sekgwa’ (village or bush). There is a broad swath of savanna — communally owned and home to numerous thorn trees, roving cows, scrub hares, mongooses, and gravel pits — a couple kilometers to the east. If I have the time and an urge to clear my head and attain a measure of tranquility, that’s my choice; otherwise I head in another direction: through the village. And that’s the route that we’re going to take on this virtual walk.

I often start at the ‘letamo’ (pond), especially if it still happens to be holding seasonal rain water, such as at present. It’s a good place to chill out and watch swallows dart and plovers and wagtails chase insects on the muddy shore. Sometimes you can catch a herd of cattle, announced invariably by their clanging bells, enjoying their last long drink and wallow of the day. If nothing else, the near shore of this little man-made pond provides a nice spot to watch the show of colors set forth in the western sky by the departing sun…and perhaps glimpse a formation of whistling ducks or cattle egrets above — as they carve patterns against the orange glow before settling onto their evening roost. After a few moments I amble on — down the oft dusty, sometimes muddy road — to stretch my legs and see what lies ahead.

'‘I fumbled ‘mongst a hundred words, but words don’t do it right…”

- Robbie Fulks

Lately, I’ve been identifying with this sentiment set out in Robbie Fulks’ wrenching ballad Alabama at Night. It seems that they often do fall short of the power of visuals to deliver full sensory and cognitive effect. So I’m going to let the pictures guide the narrative this time.

Domestic architecture

During the Apartheid period, most of Nkangala lay within the Bophuthatswana homeland, and much of the development of this residential district (including many of the homes pictured) dates to that time. Many people were relocated from ancestral areas and given small tracts of land on which to eke out a living; they generally had an acre or so of cropland, a ‘kraal’ (pen for cattle), and a cluster of domestic buildings — including living quarters, a kitchen, latrine, and outbuildings. In the case of my host family, several units were constructed over a few decades. One dwelling would be added as the family grew and savings (generated in large part by jobs in distant cities) allowed. Commercial power delivery began to reach this area in the mid-1990s, coinciding with the end of Apartheid. With the new transmission lines, transformers, and regular invoices came the means to run water pumps — enabling boreholes, tanks and plumbing to make their way to the veld. Now most families have their own well along with an electric pump to charge an elevated storage tank, and more and more enjoy indoor plumbing.

I find a real dignity in the functional, horizontally-oriented domestic structures that typify this area. These classic Tswana homes have flat or gently pitched zinc (galvanized) roofs that cover a simple three or four room layout, and many have subtly crowned or turreted facades that conceal their roof lines. An essential fixture is the ‘stopu,’ or front veranda, which is often articulated by a low wall. The ‘lapa’ — an adjoining concrete or tiled terrace enclosed by a low wall — is a classic feature on the domestic scene as well; so integral is it that the word finds itself embedded in the Setswana term for family: ‘balapa’. Regardless of etymology, they make great hangouts for humans and house cats alike — and are an essential venue for that beloved South African tradition: the braai.

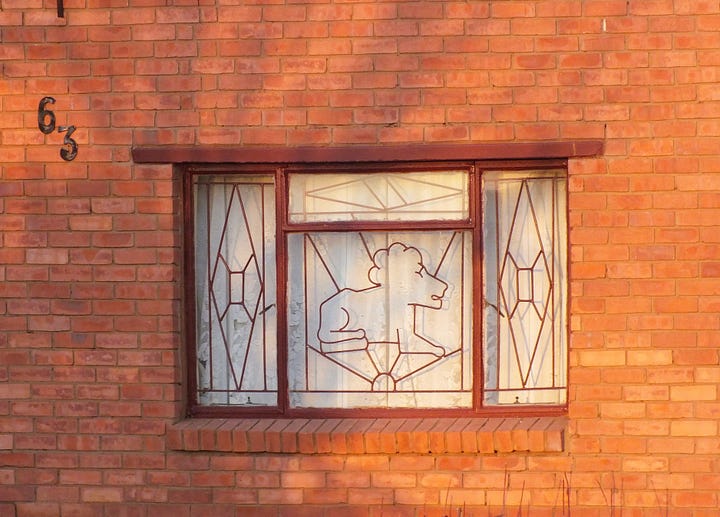

Unfortunately security is a real concern — even here in the otherwise bucolic hinterlands — and it shows in the design of domestic spaces. In addition to the ubiquitous fencing and gates, butlers (grated outer doors) and barred windows are the norm. But there is real artistry in the window bars — with almost as many designs and patterns as there are dwellings — and two are pictured above.

In recent times, some changes have taken hold on the domestic front; being only a couple of hours from the largest metropolitan area in southern Africa, and with expanded economic opportunities, the creep of ex-urbanization has reached Nkangala. You can see it in the contemporary double-story abodes — sprawling across the veld as they do — with their gabled terra-cotta roofs, satellite dishes, two-car garages and robust security fences that encompass spacious yards and gardens. Indeed, sometimes as I pass them on my daily saunters, I cannot help but to think that somehow I’ve been transposed to Emeryville, California or Fort Myers, Florida.

Commerce

In earlier times residential districts were full of bustling little stores — ‘general dealers’ or ‘tuck shops’ — which provided people with many staples in addition to convenience items. You couldn’t walk far without passing several and, indeed, this area is still dotted with these functional, boxy, one or two room constructions. Most have a few shelves — stocked with dry and canned goods, large sacks of corn meal, and maybe a tray of onions or potatoes — alongside a refrigerator with a wide selection of soft-drinks. The shopkeeper waits at a counter — often situated behind a security cage — checking out customers and dispensing sundries and refills on minutes for WiFi or cellular service or kilowatts for home power accounts.

Now a good number of these shops, such as one pictured above, are defunct — having fallen victim to the changes wrought by time and modernization. With electricity and refrigeration now commonplace, there is less of a need to run out daily for food items, and larger stores and modern retail centers have popped up near the center of town — draining neighborhood shops of vital commerce. Moreover, the risk of running a cash-heavy business in these off-the-beaten-path locations is significant, and many would-be local entrepreneurs are no longer willing to undertake such a venture for the tenuous prospect of modest margins. Those who do often have ties to other countries like Ethiopia, Somalia, and Pakistan; evidently they garner enough to justify the long distances and risks undertaken. Near the end of my walk, as dusk approaches, I sometimes pick up a liter of milk or a pack of tea from the local shop. I say ‘Dumelang’ to the patrons assembled outside — cooking chicken legs on a makeshift grill, using the local internet access, or just catching up on the day’s events. Then it’s on home — tomorrow I’ll take a different route.

Lovely piece as usual.