One thing I like to do after a day at school or at the end of the week is take a walk out onto the veld — it’s a nice way to retreat and unwind — and among the more fetching attractions of this near daily endeavor is the bird-life. Indeed one of the joys (and challenges) of getting to know this country has been to decipher the identities and habits of some of its 800 species of birds. Capturing them on the camera has been another challenge altogether, as my set-up (and patience) is limited at best, but now and then I get lucky and a winged friend of one form or another perches just long and close enough in favorable light to afford a decent shot. These frequent forays with binoculars and camera in hand are certainly not very structured or strategic, but that doesn’t detract from the fun and diversion that they provide.

South Africa, with its varied topography and climates, can be divided into several distinct eco-regions or biomes — ranging from the desolate, arid Karoo in the west to the cool, grassy highveld towards the center to the lush, humid forests along the Indian coast. Each has its own signature vegetative structure and composition, which harbors an abundance of different habitats for animals that are best equipped to exploit them. Birds are especially particular in their selection of habitats — some even down to the species of trees or types of lichen that they will use for nesting: absent those specific components you won’t find the species that depend upon them.

Savanna

Around here, as in much of South Africa’s Transvaal or northern tier, the savanna (light green on the map) dominates. Though not clear from the map, its profile changes as you move about this vast biome: from sparse and shrubby in the west, to dense and woody in the east. Basically it is the amount and seasonal distribution of rainfall that drives the composition of this and many of Africa’s biomes: with few exceptions, the more rain the more woody and complex your ecosystem will be. Here we occupy what is colloquially called the ‘bosveld’ or bushveld, a savanna that takes on an intermediate to moderately moist/dense form. Accordingly, you occasionally find birds such as woodpeckers, barbets (fruit eaters) whoopies, and others which are partial to the resources — food, shelter, cavities — most readily offered by trees.

A walk thorough our bushveld seldom disappoints; even after a year-and-a-half the sense of novelty and awe triggered by glimpsing these local birds still takes hold. That — along with the sheer abundance of species; preponderance of fair weather (and good viewing light); open spaces and vegetation that tends to be lower and scattered — makes viewing the birds a reliable treat in any season. It’s interesting, though not entirely surprising, to note the different proportions in types of birds between here and eastern North America. Groups such as shrikes, cuckoos, doves, larks, finches and ground-fowl are more abundant here. While others, including woodpeckers, warblers and ducks, are better represented over there. Of course here in South Africa we encounter many families that are not found in North America, including the charismatic sunbirds, woopoes, hornbills, rollers, barbets, and mousebirds. Some have their own taxonomically distinct ecological analogues over in the New World. The nectar-eating sunbird, for example, can claim as its the hummingbird. And you wouldn’t be so far off if you mistook a woopoe scouring the ground for bugs for a flicker; or a masked weaver crafting its pendulous nest for an oriole back home. But instead of blathering further, I’ll let the pictures tell their own stories…

Wetlands

Though there are few permanent bodies of water around here, the seasonal rains — such as we have been experiencing recently — provide temporary pools, ponds and marshes that attract a good variety of birds which are otherwise scarce on the savanna. On recent walks through the village, without even going out of my way, I could catch glimpses of marquee wetland species — including the white-faced whistling duck, red-billed teal, little grebe, African jacana, three-banded plover, blacksmith lapwing, and yellow-crowned bishop — where there had been nothing more than a baked clay-pan just weeks before. It’s a thrill to see these seasonal visitors make their returns to our corner of the veld; their numbers and duration of stay naturally will depend on the length and intensity of the rains. I’m not sure how many actually breed successfully in these ephemeral habitats, though — judging from their range-maps — it’s evident that they do find suitable homes away from the wetter low-lying and coastal areas — thus avoiding competition with the many waterbirds that inhabit those parts.

More permanent and heavily vegetated wetlands (like this one pictured in Pretoria) attract a higher diversity of waterbirds, among them some show-stoppers: South Africa’s national bird the blue crane, the grey-crowned crane, Egyptian goose and red bishop. I must admit to sometimes toting my binoculars and camera along on ‘work’ trips to the capital and wiling away a few hours on a dreary morning or two at a local bird sanctuary; it’s a great way to ease the drudgery of long days of meetings, presentations and language assessments; and it makes the prospect of a hot, cramped taxi ride to the capital a little less daunting.

‘A reyeng’ — let’s go!

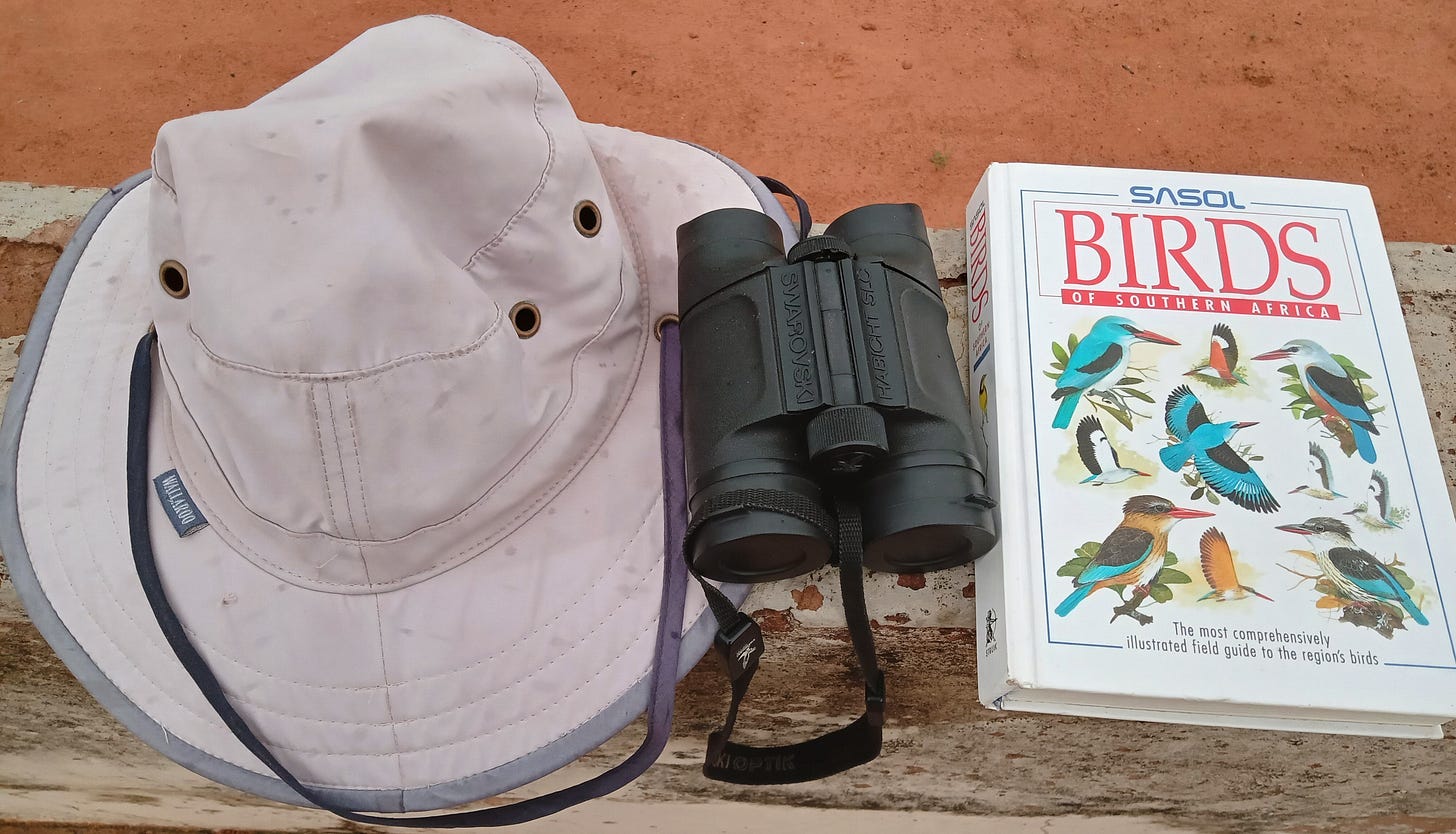

Getting beyond the leisurely enjoyment of occupying the realm of these creatures, I am trying to bring their world a little closer to the youth of our village. With few extra-curricular opportunities — apart from soccer, netball, and schoolyard games — learners are craving new means of after-class engagement and, for many, getting closer to nature really seems to resonate. Most of them have never seen a microscope, pair of binoculars or trail camera up close and — when given the chance to view their surroundings in a new way — they are intrigued, if not outright excited. Certainly my sole pair of extra binoculars and pocket field guide have gotten quite a workout as the broken neck-strap and worn-out pages can attest; almost daily at the ringing of the final bell students stream into my office pleading, “Ke kgopela verkyker” (I’d like the binoculars). And some have become quite good at tracking the weaver birds, doves, and mynas through the glass and matching them to their likenesses in the book — often rushing back eagerly to show me a picture of their latest sighting (the identification of which is sometimes a little dubious, but that’s beyond the point here). Fostering such enthusiasm and appreciation for nature serves a higher purpose than merely providing another time-eating activity: it encourages them to go deeper and read the descriptions, thus improving their English literacy and, for some, it could lead through the side door of science and math related fields. In a country with such a robust nature tourism sector — beyond the many intangible benefits inherent in engaging with the environment — there might well be practical rewards awaiting diligent young naturalists on the other side.

Quite the avian menagerie...wow! I'm late to the table for this adventure in birdlife, but it was worth the wait. I didn't see a blue crane among the photos?--I guess I'll go to Google for the national bird. So impressive Drew and, like some others, I loved hearing how the kids are engaging with such enthusiasm. Keep writing...and taking photos.

scott b

I admire how you have encouraged these kids to become interested in the birds and thus the nature that supports them I love these pictures and totally can imagine you strolling around with or without the kids on these walks.