This story is a continuation of the previous post, ‘A re tsamayeng.’

As promised this recreational walk will take us in a different direction — if only virtually. Lately I’ve been drawn by the pull of the ‘sekgwa’ (bush) when planning my afternoon capers (earlier and earlier as they have had to begin with the approach of the winter solstace). So in search of big skies, open land, and head-clearing serenity I slip out the gate and head east with the waning sun at my back. But first I have to navigate the 1.5 kilometers of worn-out asphalt road that bisects this neighborhood, ‘Legotlhong,’ (from the Setswana word for mouse; it seems that few place names around here don’t evoke animals of some kind) to reach the wide swath of undeveloped bushveld, or ‘sekgwa’ — and I usually meet a few neighbors along the way.

“When I’m in a country radically different from my own, I notice much more. It is as if I’ve taken a mind-altering drug that allows me to see things I would normally miss. I feel much more alive.”

- Author Adam Hochschild

Whoever said that you only get 15 minutes of fame evidently never spent time as a Peace Corps volunteer in rural South Africa. Although, perhaps not fame by any standard definition, sometimes I cannot help but feeling a certain empathy with life’s popular heroes, especially the reluctant ones: those born introverts who, through one twist of fate or another, have endured a good part of their lives in the public view. And thus my walks seldom take me beyond the intermittent rain of choruses: “Moshe, Moshe.” This name, Moses in the vernacular, has been my adopted one since landing in this community — and it seems that just about everyone in town knows it.

About the village

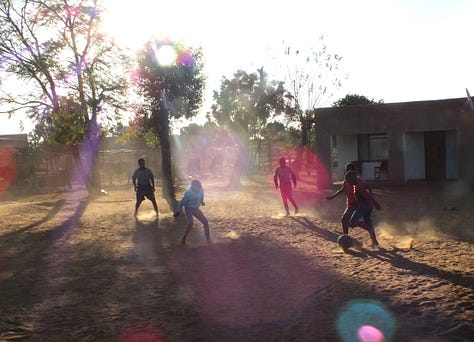

Bana (children)

The local children are the most emphatic and persistent with their cries as they glimpse me going by — often running to catch up to me for a high-five or fist pump. I have my litany of slightly corny, avuncular lines (I wonder how they really translate in Setswana) that I deal out as we meet along the road. Then it’s a parting high-five and “salang pila” (stay well). Sometimes the ball is out and I’m lured into trying my latest Lionel Messi move (not very effectively, trust me) on two or three tenacious fourth graders. While on other occasions a little shadow boxing is in order. It’s quite a sight as the local three-year-old comes barrelling through the front gate all wound up to deliver his biggest haymaker. But, happily things generally end in a truce and a perfunctory thumbs-up, and I’m on my way.

Then there’s the afternoon play group, comprising kids from two or three families, with whom I’ve developed a rather odd routine. What started as an attempt to issue a friendly fist pump from afar was returned one day with the call “Amandla,” (power) to which I felt obliged to reply “Awethu” (the power is ours). And there they were: the opening lines of a Xshosa rally cry — one that was commonly used to exhort the masses during the erstwhile freedom struggle. A strange scene indeed this must present to the unsuspecting passer-by: a graying American man engaged in an historic back-and-forth chant with a scrappy band of local kids. It’s one of those instances, I suppose, that you experience only in Peace Corps.

Not surprisingly, with options for organized after-school activities so limited, the children are quick to find other curiosities in the passing ‘lekgoa’ (white guy) — the binoculars dangling from my neck not the least of them. If I’m feeling gregarious and hands are looking passably clean, I give them a peep through my ‘verkyker,’ which often unleashes exclamations of awe has a bird, tree, fence post, or neighbor suddenly pops up impossibly large and clear. My camera is also a draw; interestingly the kids appear much more keen on striking all manner of imaginative poses and viewing the results through the little 2-inch display than in obtaining possession of any form of the image — which certainly makes matters easier.

Pastoral life

Then I move on towards the bush, usually passing a couple herds of cattle, and invariably bringing up their rear is a ‘modisa’ — cowboy of the veld. These are the heroes of my imagination, and if I were an anthropologist I suspect that they would make fascinating subjects for an ethnography. Lumbering and wiry — these stoic herders of all ages and backgrounds (some from neighboring countries) range the parched often blazing flats from sun-up to sundown looking after the bovine possessions of the townspeople. It’s little exaggeration to say that they hold together the fabric of the community: in a tradition where cattle ownership is so deeply embedded — but where cows are the objects of an entrenched and organized criminal racket — their role is paramount. And I’ve come to know a few, if not by name then by face and route. We exchange greetings in passing; I’m flattered that these solitary men of the veld remember my name and even more so that, on occasion deep in the bush, they ask me as to the location of their errant cows (with no GPS or radio locators, bells and word-of-mouth are still key to keeping your herd intact). Desperation perhaps, I cannot help but to construe in such queries a modicum of social acceptance.

I continue deeper into the veld, often seeing no one else and hearing not a sound but distant cow-bells pealing or go-away-birds squawking. This brushy expanse of sandy plain is the provenance of the Bakgatla tribe. It seems that all enjoy the right to use it to their liking — to meet the needs of their households if little more. And along the dusty track I am frequently passed by a donkey drawn cart loaded high with limbs to be chopped and fed to the cooking and water-heating fires of the village ahead. Sometimes a passing wagon is heavily burdened by a substantial heap of red gravel excavated from pits in the sedimentary strata a couple of kilometers up the road. This location, on a low rise, often forms the terminus of my adventure. From here — bathed in the soft hues of the afternoon sun — the views of the outlying Sepedi villages and the high-veld plateau rising in the distance are sublime. But I cannot hang around: its a 45-minute walk back and here, at these lower latitudes, darkness comes quickly.

On the veld

On retreat back through the village I salute the residents milling about at the end of the day. It a community where car ownership is uncommon, the roads are filled with pedestrians returning from their day’s travails: women toting bags of groceries or balancing sacks of beans on their heads; laborers in jumpsuits schlepping back from the job; residents pushing wheelbarrows under burdens of fuel wood; landscapers passing with bow-saws on their shoulders; youth, slings in hand, on their way out for a late rabbit hunt; and vendors pedaling by with their wares (brooms, mops and rakes) precariously perched atop their bikes. Some of these enterprising peddlers even manage to transport their merchandise of plastic water drums — a popular consumer item at the onset of the dry season — on their bicycles, and — in order to leave no potential market untapped — offer no-interest credit plans, the only documentation necessary is an entry in the ledger they carry.

In a day’s work

I’ve become acquainted with some of these folks over the past year and we typically exchange a word or two. Like everywhere it seems, the weather is a popular subject; lately I’ve been hearing a lot of ‘go a tonya!' (it’s cold!). And they often express curiosity as to my intentions as I head out at the end of the day with binoculars hanging from my neck; few people here would do something so apparently frivolous at such an hour, and I’m sometimes admonished: ‘tlhokomela — ke bosigo’ (be careful — it’s evening). But I think people have become resigned to the notion that Moshe will do what Moshe does — that by now I’ve developed a level of comfort about this place — and we soon move along in our respective directions. Just recently, on my way home with dusk in fast pursuit, I encountered a parent of a learner at our school who was unsure of her whereabouts and asked me for assistance. I couldn’t help but to take away a slightly smug sense of satisfaction as I turned her around and got her headed back in the right direction. Perhaps, at least to some degree, I have arrived.

Hey Drew, hope you enjoyed a good birthday ♥️

Drew--Artful in so any ways and your keen eye and ear serve you (and us) well!